“Each day in the United States, approximately 9 people are killed and more than 1,000 injured in crashes that are reported to involve a distracted driver”.

What Is Distracted Driving?

Distracted driving is any activity that diverts attention from driving, including talking or texting on your phone, eating and drinking, talking to people in your vehicle, fiddling with the stereo, entertainment or navigation system—anything that takes your attention away from the task of safe driving.

Another frequent question is whether talking on the phone is really any more dangerous than putting on mascara, shaving, or reading a map while driving — all things we’ve seen drivers do. I reply that indeed, any activity that distracts a driver visually or cognitively increases the risk of an accident. (And for clinicians, that includes dictating.) It’s just that cell-phone use is far more widespread than these other activities. But none of them is safe.

More...

Texting is the most alarming distraction. Sending or reading a text takes your eyes off the road for 5 seconds. At 55 mph, that's like driving the length of an entire football field with your eyes closed.

The statistics are chilling. In 2011 (the last year with complete statistics), 3,331 people were killed in motor vehicle crashes involving a distracted driver, and nearly 400,000 were injured within the USA The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration estimates that distracted driving accounts for about one in five crashes in which someone was injured.

You cannot drive safely unless the task of driving has your full attention. Any non-driving activity you engage in is a potential distraction and increases your risk of crashing.

There are three major types of distraction: visual distraction (taking your eyes off the road), manual distraction (taking your hands off the wheel), and cognitive distraction (taking your mind off the complex task of driving).

Imagine the scene: three young women are traveling in a car. It is a sunny morning, traffic is light, and all are wearing their seat belts and are not intoxicated. They are talking about a friend — “You like him, don't you?”

It is happy, benign teenager chatter. Then the driver decides to include that other friend in the conversation. While steering, she sends him a short text message on her cell phone.

Suddenly, the car swerves into oncoming traffic and metal hits metal at high speed. Bodies are thrown. Glass breaks. Blood splatters. When the car finally comes to a stop, only the driver is conscious. Her screams speak of not only the agony of her injuries but also the realization that she has just killed her two friends — by texting.

This scene appears in a British public service announcement. The video above is horrifying to watch, but although it is obviously staged, the scenario is hardly a fiction: driving while distracted — by talking or texting — increases the likelihood of accident and injury. And some of these accidents kill people.

Although it is difficult to assess the absolute increase in the risk of collision attributable to driver distraction, one study showed that talking on a cell phone while driving posed a risk four times that faced by undistracted drivers and on a par with that of driving while intoxicated.

Another study showed that texting while driving might confer a risk of collision 23 times that of driving while undistracted. Although there are many possible distractions for drivers, more than 275 million Americans own cell phones, and 81% of them talk on those phones while driving. The adverse consequences have reached epidemic proportions.

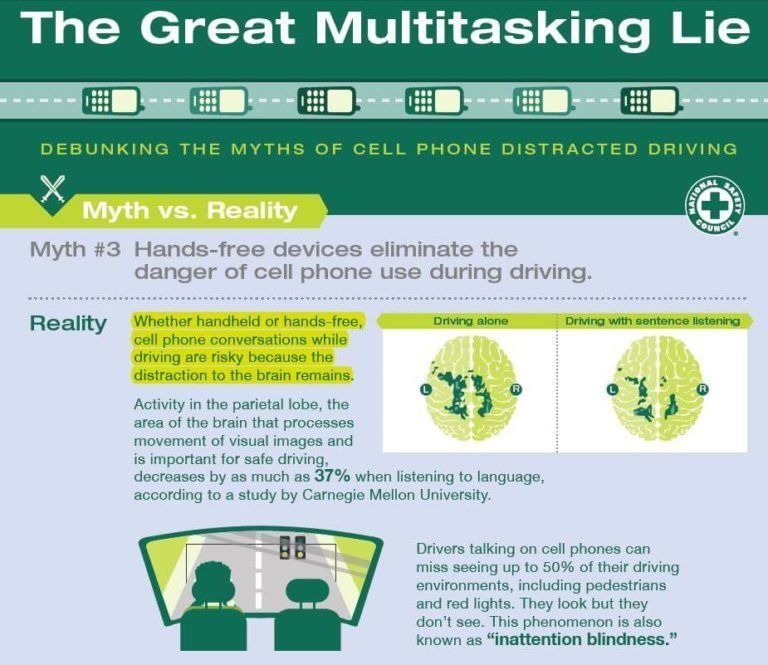

Current data suggest that each year, at least 1.6 million traffic accidents (28% of all crashes) in the United States are caused by drivers talking on cell phones or texting. Talking on the phone causes many more accidents than texting, simply because millions of more drivers talk than text; moreover, using a hands-free device does not make talking on the phone any safer.

according to the National Safety Council:

- Drivers talking on handheld or hands-free cell phones are four times as likely to be involved in a car crash.

- People talking on cell phones while driving are involved in 21% of all traffic crashes in the U.S.

In addition, hands-free devices do not eliminate the danger of cell phone use during driving.

Acknowledging these risks, all but 11 states have passed laws regarding cell-phone use while driving. And the U.S. government is concerned: in January 2010, the secretary of transportation and the National Safety Council announced the creation of FocusDriven, an organization devoted to reducing the prevalence of distracted driving. The Department of Transportation has also launched a Web site, www.distraction.gov.

At the medical school and academic practice where I teach, students and residents routinely query patients about habits associated with harm, asking about the use of helmets, seat belts, condoms, cigarettes, alcohol, and drugs.

There is little solid evidence that asking these screening questions has any benefit. But we continue to ask them — as I believe we should. And as technology evolves, our questions must be updated in keeping with the risks: it's time for us to ask patients about driving and distraction.

Although no direct correlation can be made, we know that counselling patients about dangerous behaviours can have powerful consequences. According to the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, even 3 minutes spent discussing the risks of tobacco use increases the likelihood that a patient will quit smoking.

Context matters. When a doctor raises an issue while providing overall preventive care, the message is different from that conveyed by a public service announcement nestled between ads for chips and beer or a printed warning on a product box.

Recently, I have added a question about driving and distraction to my annual patient review of health and safety. I begin with the customary seat-belt question.

Then I ask, “Do you text while you drive?”

Although I'm concerned about both texting and talking, most people are aware of the risks associated with texting, and many judges it more harshly. If a patient admits to texting while driving, I share my knowledge and concerns. Many patients who do not text while driving voice opinions about its dangers, giving me an opening to note that talking on the phone while driving causes more accidents than texting.

Although I can share published data and often recommend that patients view the video described above, I find it more powerful simply to say that driving while distracted is roughly equivalent to driving drunk — a statement that captures both the inherent risks and the implied immorality.

Amy N. Ship, M.D. ask patients whether they could reduce or abstain from cell-phone use while driving. As with any plan for behaviour modification, we need to understand the circumstances surrounding the activity.

Many people have become accustomed to the diversion of talking on the phone while driving, and we're all susceptible to the allure of a new message or call. If patients tell me that occasionally they receive “important” phone calls they don't want to miss, we discuss what that means in the context of the risks. We talk about alternatives, including pulling over to make or take calls.

I remind them that we all managed without mobile phones until recently and encourage them to return to the practices of the pre–cell-phone era.

Inattention blindness

Psychology faculty members Jason Watson, Ph.D., and David Strayer, Ph.D., used a video that was created for earlier inattention blindness research featured in the 2010 book The Invisible Gorilla by Christopher Chabris, Ph.D.

The video depicts six actors passing a basketball, and viewers are asked to count the number of passes. Many people are so intent on counting that they fail to see a person in a gorilla suit stroll across the scene, stop briefly to thump its chest and then walk off.

This experiment reveals two things: that we are missing a lot of what goes on around us, and that we have no idea that we are missing so much.

According to previous University of Utah research, only 2.5 percent of individuals can drive and talk on a cell phone without impairment. And Strayer has conducted studies showing that inattention blindness explains why motorists can fail to see something right in front of them – like a stop light turning green – because they are distracted by the conversation, and how motorists using cell phones impede traffic and increase their risk of traffic accidents.

What can drivers do if they want to fill the resulting void?

They can listen to the radio or a CD?

They can pay attention to what they're doing and their surroundings, rather than attempt to multitask. We talk about practical solutions. I tell them about a driver who killed a woman while talking on his phone but couldn't restrain himself even after that horror. He now puts his phone in the trunk of his car before he gets behind the wheel. I talk about creating such a system for eliminating the risk.

Although I've encountered less resistance from patients than I'd anticipated, many do have questions. Most commonly, they ask why talking on the phone, even with a hands-free device, is more dangerous than talking to a passenger in their car.

There are several reasons: first is the obvious risk associated with trying to manoeuvre a phone, but cognitive studies have also shown that we are unable to multitask and that neurons are diverted differently depending on whether we are talking on the phone or talking to a passenger.

When patients aren't convinced, I ask them,

“How would you feel if the surgeon removing your appendix talked on the phone — hands free, of course — while operating?”

This hypothetical captures the essence of the problem — the challenge of concentrating fully on the task at hand while engaged in a phone conversation.

In 1959, before seat belts were standard equipment in cars, my father — a surgeon who was an active member of Physicians for Automotive Safety in its infancy and had seen the terrible consequences of motor vehicle accidents — had airplane seat belts installed in our family Studebaker.

Vehicular safety was thus part of my education before I was in grade school. Fifty-plus years later, laws enforce seat-belt use in nearly every state, and deaths from motor vehicle accidents have decreased markedly.

Just as we've moved beyond Studebakers, it's time for us to update our model of preventive care. Primary care doctors are uniquely positioned to teach and influence patients; we should not squander that power.

A question about driving and distraction is as central to the preventive care we provide as the other questions we ask. Not to ask — and not to educate our patients and reduce their risk — is to place in harm's way those we hope to heal.

UK Penalties Law

You can get 6 penalty points and a £200 fine if you use a hand-held phone when driving. You’ll also lose your licence if you passed your driving test in the last 2 years.

You can get 3 penalty points if you don’t have a full view of the road and traffic ahead or proper control of the vehicle.

You can also be taken to court where you can:

- be banned from driving or riding

- get a maximum fine of £1,000 (£2,500 if you’re driving a lorry or bus)

Reference

June 10, 2010

N Engl J Med 2010; 362:2145-2147

https://www.nhtsa.gov/risky-driving/distracted-driving

https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/distracted-driving-were-number-1-201303155980

https://www.cdc.gov/motorvehiclesafety/distracted_driving/index.html

http://www.theinvisiblegorilla.com/gorilla_experiment.html

https://keepontrucking.net/roadside-eye-catchers-drive-motorists-to-distraction/