Every company policy state that if you drink on the road your job will be terminated. Also, if any alcohol is found in your truck by your company your employment will also be terminated. Most of the major transport companies also have a mandate that all drivers involved in a road traffic accident will need to take a compulsorily drug and alcohol test. The consumption of alcohol is prevalent amongst professional drivers and stress has been linked to the increase in consumption.

More...

Many drivers do not appreciate that they are still over the legal limit during the following day. However, a current documentary by Radio and TV presenter Adrian Chiles highlighted the long-term damage alcohol has on your health.

A current documentary included Proofessor Roger Williams from the Institute of Hepatology at King's College Hospital in South London, has given his life to medicine and is widely revered as the “Sir Alex Ferguson of the medical establishment”, and his driving passion is to dispel our blasé attitudes to casual, excess drinking and face up to its real cost.

A speech made a few weeks ago by the Secretary of State for Health, Matt Hancock read:

'For 95 per cent of people, the alcohol we drink is perfectly safe and normal. I like a pint or the odd glass of wine, and I know I speak for most of my audience and certainly the vast majority of my colleagues, too.'

We must also need to point out that alcohol plays an important role in the lifestyles of European citizens and cultures of European countries. Alcohol is also an important driving force behind the European economy that creates jobs, generates fiscal revenues and contributes to the UK and EU economy by around €9 billion annually through trade (Anderson & Baumberg 2006)

WHAT riled Professor Williams was that first sentence? For while the Health Secretary may think 95% of alcohol consumption is safe, Professor Williams and fellow experts on the influential Lancet Standing Commission on Liver Disease in the UK do not.

They are committed to lobbying the Government and public health policy makers to act, especially on the availability of cheap drink.

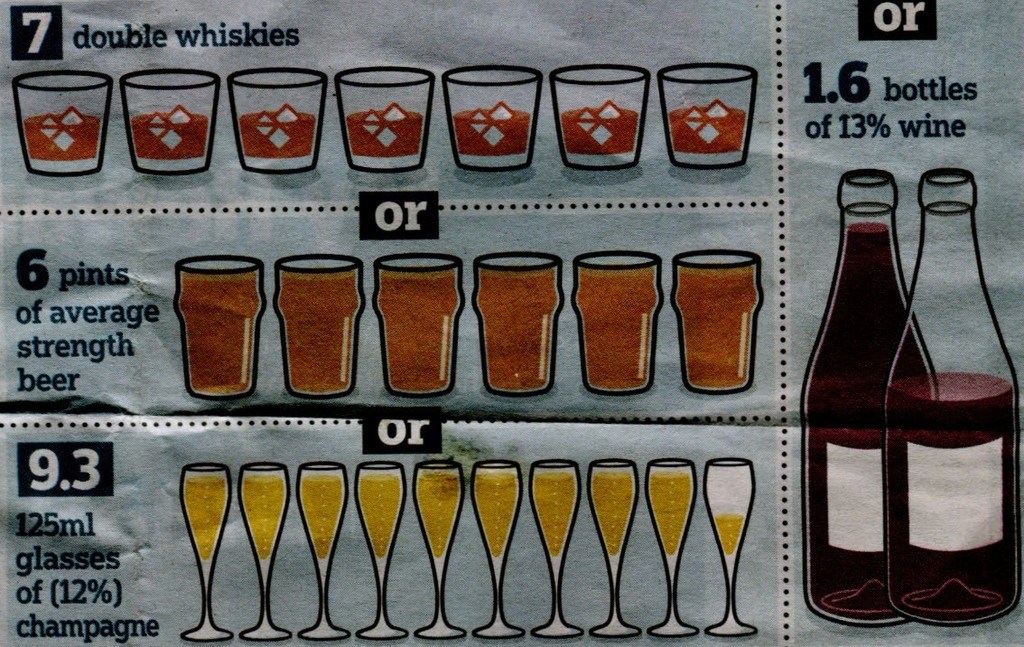

The NHS recommends that adults drink no more than 14 units each week — that's 14 single shots of spirit or six pints of beer or a bottle and a half of wine.

But about a third of drinkers consume more than this, which is enough to significantly damage their health, particularly their liver.

The reporter used to be a bit of a drinker, often knocking back six pints of Guinness a day. In an average week, I'd consume around 50 units, although that number was known to double.

I did my best to downplay and told himself everyone likes a drink. (But that's not true, since about 17 per cent of adults don't drink at all and 70 per cent of those who do stick to the 14-unit guidelines.) The only days I drank nothing focus on extreme cases, and so the rest of us look at the classic 'alcoholic' slumped in a shop doorway, and say to ourselves: 'Oh, that's not me!

Therefore, I have no problem.

I am fine.'

Well, I know now that we aren't fine. Today, as someone who still likes to drink, nothing when he was broadcasting in the evening. He needed an actual reason to abstain for even one day. His drinking habits go back a long way. At university, if anyone I liked had said they didn't drink, well, I probably wouldn't have ended up being friends with them.

And as a lifelong West Bromwich Albion fan, going to a match meant having a few drinks with mates — one or two or countless — beforehand.

I believe the word 'alcoholic' is outdated, but I've come to realise that I was undoubtedly dependent on alcohol to some extent.

And if I am, then thousands of others are, too. They are drinkers like me, quietly putting it away without, superficially, doing any great harm — when, actually, we could do ourselves some real good by drinking significantly less.

I believe that all the coverage of alcohol misuse and abuse fails to tackle this problem. It tends to focus on extreme cases, and so the rest of us look at the classic 'alcoholic' slumped in a shop doorway, and say to ourselves: 'Oh, that's not me! Therefore, I have no problem. I am fine.'

Well, I know now that we aren't fine. Today, as someone who still likes to drink, nothing would give me more pleasure than to tell you that the 14-unit figure is a load of nonsense.

But I can't do that. Over the past months, I've applied my (admittedly unscientific) mind to a vast amount of evidence, and it is clear that the folks in white coats speak the truth: drinking more than 14 units a week is bad for you.

To suggest otherwise is about as daft as claiming that smoking isn't harmful.

To be fair to Matt Hancock, he's right when he points out that the group most at risk of alcohol-related health problems is the 5% of drinkers who put away more than 50 units a week (for women, who are more susceptible to damage caused by alcohol, it's 35 units). Indeed, this group consumes about a third of all the alcohol drunk in the UK.

But look at it another way and you discover that nearly half of all alcohol is consumed by the 8.5 million drinkers like me who knock back between 14 and 50 units a week.

More than one million hospital admissions annually are the result of alcohol-related disorders, and it costs the NHS £3.5 billion a year.

Alcohol is the biggest risk factor for death in men under 60.

And terrifyingly, with the frequency of deaths from liver disease and hospital admissions increasing year on year, logic dictates that must include many of those drinking between 14 and 50 units a week. From all I have learned about fullblown liver disease, the symptoms are horrific and the end ghastly.

Just as worrying is the demonstrated link between drinking arid the increased risk of common cancers of the breast and bowel. All of this becomes even more alarming when you realise — as I did when making the documentary for the BBC — that it's very easy to drink 50 units a week if you drink something every day and then throw in a couple of big nights out.

At a friend's 40th birthday celebration last year, I drank four pints of Guinness, four bottles of beer, a glass of champagne and five glasses of wine. Even a quiet night out — what I, in my ignorance, thought of as a non-drinking night with a mate — would be two pints of Guinness each and perhaps a bottle of wine between us.

Even with that degree of regular boozing, the symptoms can be silent. Liver disease often doesn't show itself until it's too late to easily treat.

Routine blood tests showed my liver function was normal, but for the documentary I had a fibroscan which is a type of ultrasound that assesses the hardness of the liver. That told a different story.

My liver is fatty, which is bad, and there are signs of fibrosis caused by a large amount of scar tissue — both undoubtedly linked to my drinking. In short, last year I found I was well on the way to having potentially fatal liver disease.

The liver specialist I saw said: 'You can't go on like this' — and he was right.

For you, it's not a choice between living a good, long life or a good, slightly shorter life, he added; it's about making your declining years as bearable as possible. And drinking too much before you get there isn't going to help.

Ironically, my biggest concern is getting to old age without having ruined my innards so much that I can't enjoy a drink to ease me through my twilight years.

So, I've cut down on my drinking, though it's not been easy. In fact, I wonder whether it's easier to stop completely rather than to try to moderate what you drink. If you stop completely, you have only one decision to make, hard though it is. But you know where you stand, and so does everyone else.

If you're merely moderating, there are dozens of decisions to make every week. When do I drink?

How much do I drink?

Will this friend or that friend be annoyed if I don't drink with them?

The list goes on and on.

But I'm proud to say that I've managed it. And, for me, the key to it has been counting units. Believe me, I know how hard it is to bring yourself to do this, and I resisted for a while.

I find the Drink Less phone app easiest to use (other apps are available). It allows you to input your alcohol intake throughout the day and projects it onto a graph. The effect on me was immediate.

I've discovered that once you're counting units, you can work out which drinks you really want, or need or will enjoy.

I reckon if you put every drink I've ever consumed in a row, it would stretch for nearly four miles. But, to be honest, I think I've only really appreciated a third of them. The rest were completely unnecessary, and now I've got a dodgy liver for my trouble. What an idiot!

Nowadays, when I go to the pub, I order what the Germans call beer sour: half a beer and half a soda water in the same glass.

That's been a game changer for me. It gives you a pint to hold and the taste isn't dramatically different. More importantly, it's half the units. I've also started drinking alcohol-free versions of the drinks I like, and there's plenty of good stuff out there.

So how do I feel in my new guise as a 'moderating drinker'?

Well, I'm a bit lighter, a bit calmer, a bit healthier and, what I do drink, I enjoy more.

The biggest changes I've noticed, however, are psychological. The pressure we put on each other to drink is absurd. Alcohol is the only drug you must apologise for not taking. I've sworn a solemn oath no longer to be pressured into drinking by anyone, and nor will I pressure anyone else.

But neither will I pressure anyone into drinking less. If you enjoy every drop, crack on —just if you're aware that more than 14 units a week puts your health at risk. Don't beat yourself up if you can't get down to that number. I still really struggle, but every unit I don't drink helps.

If you're regularly drinking much more than that — say 40 units a week — my strongest advice is to ask your GP to send you for a fibro-scan. I know how lucky I am. I got the wake-up call I needed. Now, I want to wake-up others.

And if I ever need further encouragement, I can always call upon the image of Professor Williams slumped at his desk in despair, knowing better than anyone what too much booze is doing to us — and determined to do something about it.